Freespace

Remarks on the Collison-Cowen-Call for New Aesthetics

The entrepreneur Patrick Collison and the economist Tyler Cowen „are seeking to fund artists, architects, and designers who are consciously working to define New Aesthetics.“ Their call combines a descriptive formulation with a normative one: „what is the aesthetic of the twenty-first century?“ and „what should the future actually look like?“1 While the call may be read as an inventory, aesthetics that are already ubiquitous will not be funded. Instead, the initiators want to be surprised and inspired.

Barely two weeks after its publication and without any fellows yet appointed, the call has already made an impact: it sparked a discussion about the prerequisites for new aesthetics in the 21st century, to which, among others, Stephanie Wakefield and Paul Jun have contributed with engaging articles. What makes Wakefield’s and Jun’s contributions so interesting is that they avoid focusing on specific features of a contemporary aesthetic, but instead inquire into the very preconditions that make such an aesthetic possible in the first place. I’ll pick those threads up in a minute.

Presuppositions of the call for New Aesthetics

But first, let’s take a step back and reflect on the call’s underlying assumptions:

The authors are impressed by the Bauhaus’s success as an era-defining aesthetic in the 20th century. However, they do not conceal its widespread unpopularity, and Tyler Cowen adds, „that beauty can be found in strange and unusual places.“ Doesn’t this not only suggest that aesthetics is not confined to beauty, but also that beauty is less likely to be produced by manifestos and planning than to emerge indirectly when circumstances are favorable?

Can the idea of an aesthetic time signature remain plausible when the world is both deeply diverse and many countries no longer regard a Western-inspired ‘international style’ as an attractive goal?

Can the aesthetics of an era be recognized within that very era, or only in retrospect, when the owl of Minerva begins its flight in the darkness?

Conversely, the call’s initiators don’t want to be bored with already widespread aesthetics. But what if these very artefacts (like intentionally hidden, nondescript server farms or crappy interfaces of computerized homes) represent the defining aesthetics of our time?

Finally, assume the pro-novelty streak implicit in the invitation is failing to recognize that the newness has become an obsolete criterion, and that—after exhausting every possibility—the genuinely new emerges from reworking what already exists? Would it then still make sense to search for new aesthetics?

Don’t get me wrong. I’m bringing up these questions not out of skepticism about the call, but to prepare a reframing of its original question.

Beyond styles

By making clear that a new aesthetic does not arise by creating a specific style, Stephanie Wakefield and Paul Jun have addressed a key issue. Styles are subjective. Styles become dated, styles turn formulaic. Styles are challenged by new circumstances, for example, when the poor energy performance of Classical Modernism becomes apparent or when the charm of the Meisterhäuser can no longer be felt amid the harshness of low-quality mass housing.

New aesthetics must be more than style — “neither message nor sign,” as Peter Zumthor puts it.2 What is mere assertion, what is mere expression, what is mere signaling, can be sorted out: “retrofuturistic aesthetics” (which Collison and Cowen themselves exclude), historicizing facades, deceitful decor, an artist’s vain particular obsessions, dreary corporate buildings, showy gestures, greenwashing, and so forth.

If style is no longer interesting, then what? Jun and Wakefield present two differing proposals: „story“ and „conditions“.

Story and form

„The future does not arrive as an aesthetic. It arrives as a story strong enough that people start rebuilding their lives to match it.“

In his view, a new aesthetic derives from a “shared story” that envisions a positive future life:

„Maximum support for children, parents, education, and clean water. Objects that don’t just perform, but belong. Buildings that don’t just impress, but hold us. Interfaces that don’t just convert, but teach people to see again. A future that doesn’t look like a spaceship, but feels like a place worth embodying.“

By moving the emphasis from purely aesthetic concerns to clarity in diagnosing the present and to ethical guidance, Jun rightly avoids aestheticist shortcuts. The price for this, however, is that the form side remains largely untreated. What would, e.g., an ecological aesthetic look like? Apart from clarity about the right direction, what is necessary to design it?

Conducive circumstances

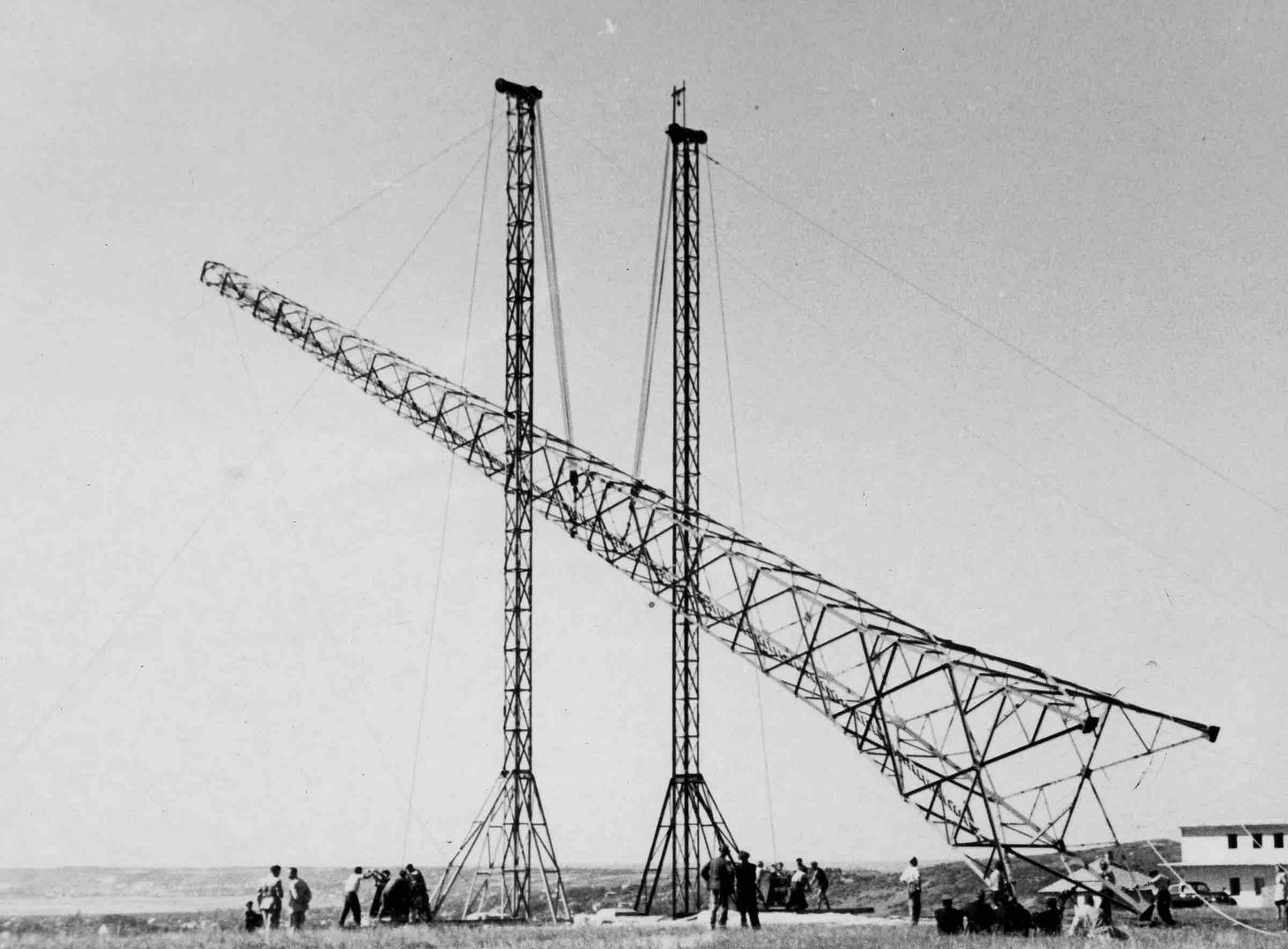

This is where Wakefield kicks in. She is less interested in the ‚what,‘ but rather the ‚how.‘ This ‘how,’ she argues, stems from a twofold movement: a distancing from the obsolete (she cites Italian Futurism) and the development of the new (illustrated by the early Bauhaus). According to Wakefield, the early Bauhaus „rebuilt the perceptual and conceptual conditions under which new forms could become thinkable again.“ These conditions included „pedagogy, shared conversations, parties, and overall experimentation.“ Exercises and „structured investigations“ such as „the Vorkurs, workshops, and performance“ served to explore and experiment. They „functioned as a laboratory organized around shared inquiry rather than stylistic or ideological coherence.“ In this spirit, she recommends real-world experimental zones that provide space and time for the emergence of a new aesthetics.

I agree, but I think she hasn’t taken her perspective far enough. Interestingly, Wakefield chooses two European examples rather than the Black Mountain College, where Bauhaus emigrants brought the early Bauhaus ethos to America. Jun also doesn’t mention the BMC, but merely refers to Walter Gropius’s influence on Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. This is unfortunate, as that particular school, which operated in North Carolina from 1933 to 1957, can teach us something when searching for a new aesthetic.

When art crosses over into life

At the BMC, Bauhaus masters such as Anni and Josef Albers, Lyonel Feininger, and Walter Gropius taught, alongside American avant-gardists like John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Buckminster Fuller. Notable students included Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. When I recently taught a seminar on the BMC at the Berlin University of the Arts together with a colleague from painting and students from fine arts, design, architecture, and communication, we were guided by the question of how this school might inspire our work. We took a deep dive into historical curricula, firsthand testimonies, and other primary sources. Our working hypothesis was that the BMC functioned as a self-correction of (parts of) the Bauhaus, which, as it grew more successful, increasingly abandoned the open-minded spirit Wakefield rightly points to as characteristic of its early years.

The Black Mountain College was the kind of place Wakefield pictures, though with a distinctive twist:

“The idea was not to produce artists per se (...) but thinking citizens who, honed by the discipline inherent to the arts, were capable of making complex choices — about their own work and, ultimately, in the larger world.“

Experimental practices, transdisciplinary research, and above all, communal living did not serve to develop a particular aesthetic, but rather to cultivate a specific way of life through the aesthetic:

“Black Mountain College was less an institution than a situation.“

This ‚situationality’ that Helen Moleswort3 highlights, included, among other things, Josef Albers’ perception exercises, a generous approach to time, and a certain purposelessness.

What does this mean for the re-framing of the search for a new aesthetic? It means the question should no longer be where the avant-garde is, but when4 What matters about an avant-garde is neither its rejection of tradition nor its will to form, but art crossing over into life.

Freespace

New aesthetics shouldn’t be concerned with mirroring the spirit of the times or creating a new stylistic community; instead, it should seek to contribute to lived experience in a particular way. In contrast to Jun, I believe this doesn’t require agreement on a grand narrative. In contrast to Wakefield, I take the experimental turn to be not only a method for producing outcomes but the outcome itself: an aesthetics of opening up.

Take architecture and design, for example. In his 1965 critique of functionalism, Theodor W. Adorno insisted that architecture „should produce something that comes out of the space, rather than place something arbitrary within it.“5 As early as his 1951 Minima Moralia, he had pointed out that things designed merely for function tend to take on a shape that „restricts interaction with them to mere handling, tolerating no excess, whether in freedom of behavior or in the independence of the thing.”6 It is remarkable that Adorno highlighted both the ‘ecological’ intrinsic worth of the material and the ‘liberal’ surplus of freedom attached to usage. What matters is how material is treated and which aspects of being human an artifact stimulates.

In 2017, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, founders of the Dublin firm Grafton Architects, published their Freespace Manifesto. It reads like an attempt to make Adorno’s thinking more concrete. It celebrates an architecture of generosity, in the very sense that Alexandre Lefebvre pointed out that the word liberal has a dual meaning: „to be free and to be generous.“

“FREESPACE describes a generosity of spirit and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture’s agenda, focusing on the quality of space itself.

(...)

FREESPACE celebrates architecture’s capacity to find additional and unexpected generosity in each project - even within the most private, defensive, exclusive or commercially restricted conditions.

(...)

FREESPACE provides the opportunity to emphasise nature’s free gifts of light - sunlight and moonlight, air, gravity, materials - natural and man-made resources.“

The Town House at Kingston University London, designed by Farrell and McNamara, masterfully transforms the manifesto into a building:

Architecture like this doesn’t reserve the free space, pioneered by the early Bauhaus and Black Mountain College, for the development of prototypes. It infuses everyday life with aesthetic sensibility. Instead of waiting for the next big thing, it gets straight to work and makes the transformative energies of aesthetic practices available right here and right now. The New Aesthetic should be an aesthetic that weaves focused perception, sensory contact, and shifts in perspective into life. It brings the liberating power of the arts into the everyday.

Emphasis mine.

Peter Zumthor: Architektur Denken. 2nd edition, Basel 2006.

Helen Molesworth, Leap Before You Look. Black Mountain College 1933–1957, Yale 2015.

The credit for this phrasing goes to Franz Liebl and his brilliant book Steakholder Management. Bausteine eines Culinary Turn in der Strategie, Berlin 2024.

Theodor W. Adorno: “Funktionalismus heute”, in: Ohne Leitbild. Parva Aesthetica, Frankfurt/Main 1967, p. 104 – 127.

Theodor W. Adorno: Minima Moralia – Reflexionen aus dem beschädigten Leben, Frankfurt/Main 1951.

I’m not a cultural studies scholar, but this much seems clear to me: aesthetics don’t emerge in a vacuum. It only make sense within a specific way of life. Remove that context and what’s left is decoration, or at worst kitsch.

The Bauhaus is a good example. It wasn’t just a style, it was also a social movement. In that context, it probably had real aesthetic force. I’m not disputing that. But it doesn’t follow that importing the associated architectural style automatically made our lives better. Once you detach the form from its context, “function before content” can quickly turn into concrete housing wastelands.

If that’s roughly what you meant, we’re probably on a similar page.