When moving into my new office

Regarding inheritance

A few days ago, I relocated to a new office. The former occupant, a now-retired colleague I highly value, left an empty space; only a well-lit can of Campbell’s Tomato Soup stood out on a shelf.

A fresh start – and yet, the move from my interim office to the final one turned my thoughts towards the past. What does it mean to take on an inheritance built by a previous generation, especially one renowned for its extraordinary accomplishments?

Anyone who sits in an office has „a position,“ is „entitled,“ and gets paid. I’m finally here, and the task before me is to make the most of this privilege. There’s no starting from scratch, though, and as far as I’m concerned, that’s a good thing. My predecessor outfitted the office during the boom years with items that my university, now under financial strain, would find unaffordable. I benefit from his taste. Just as the 1893 building where my office is located, the lighting, shelving, and furniture exhibit a sustainability that predates the concept, even though they were likely considered extravagant when they were built and acquired.

I’m not just inheriting high-quality premises, though, but also the spirit of the 1990s, the era when my colleague began his career. Freddie deBoer put it perfectly in one of his finest articles:

„The 90s were better. (...) there was a modern sensibility without all of the pathologies of the internet (...) You used to do things and have places to do them. (...) There was optimism about the coming of the new millennium before we found out what a rotten time the next couple decades would be.“

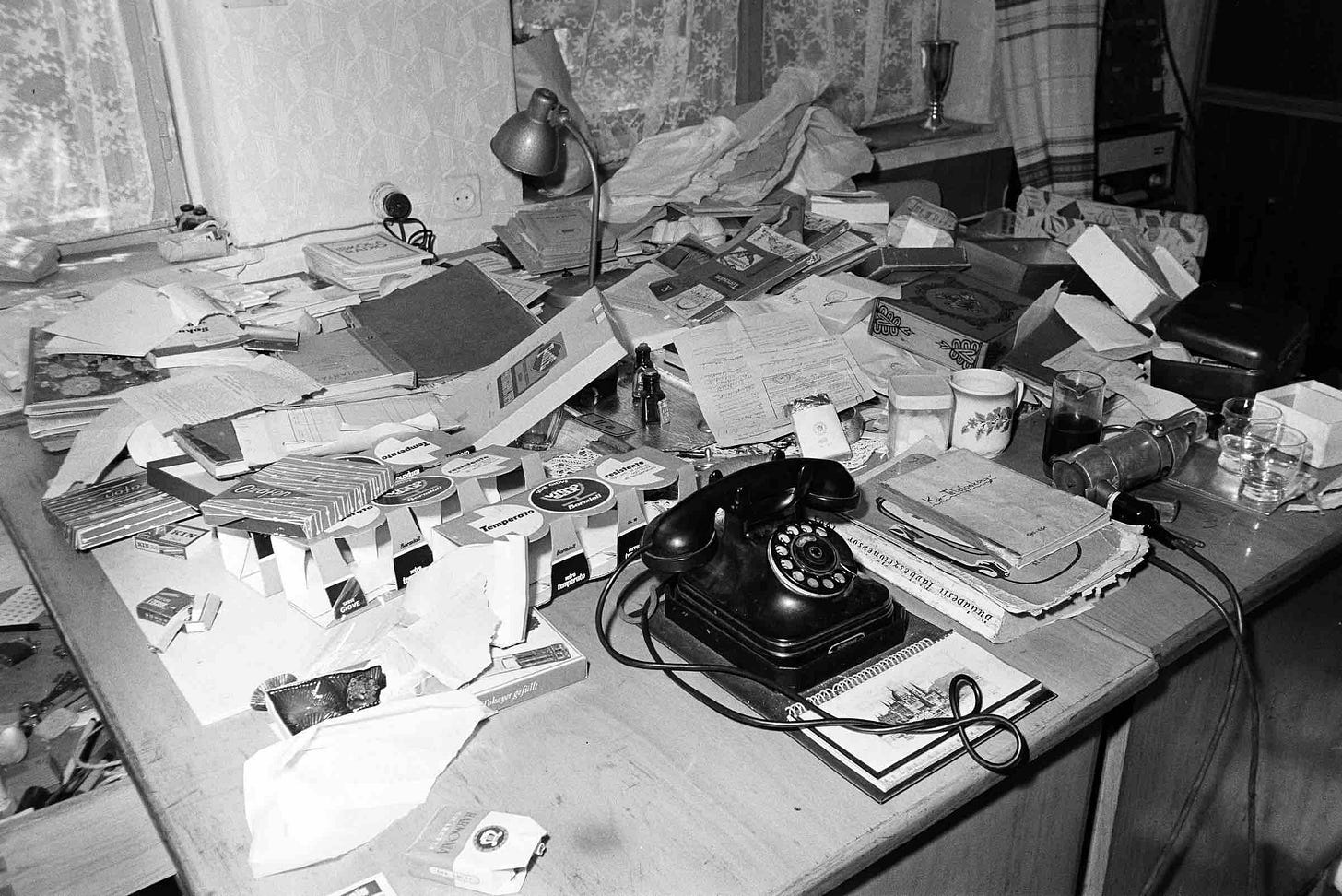

Leafing wistfully through my colleague’s papers from the 90s and 00s, I envision an era when thinking was as thorough as it was unrestricted. A period that was all about the new, about creativity. Trend analysis was exciting back then, pop, innovation – terms that today seem remarkably stale, flat, and bland.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. In an aging society constrained by austerity, in a time when freedom is fragile and contested, different modes of thought are required: more grounded in daily life, more serene, and finding potential in what is already there—a return to newly considered origins, to existing elements uniquely reinterpreted.

My colleague has traced this change in his latest writings, rather than lamenting the (allegedly) carefree years. In his sensitivity to the deep-seated shift that concerns us today, I see a third legacy, alongside the tangible assets and the intellectual accomplishments of the prosperous years. The most important thing for us to inherit from the preceding generation is their cultivation of a particular way of being in the world. It precedes all concrete achievements. It makes remarkable accomplishments possible in the first place. And holds up well in more challenging times: curiosity about the world, quirkiness, tenacity, and the ability to leverage opportunities.